Math 185: Complex Analysis

Table of Contents

- Lecture 1: Introduction (January 21, 2026)

- Lecture 2: Operations on $\mathbb{C}$ (January 23, 2026)

- Lecture 3: Multiplication and Polar Coordinates (January 26, 2026)

- Lecture 4: Complex Functions (January 28, 2026)

- Lecture 5: Complex Inverses (January 30, 2026)

- Lecture 6: Graphing Complex Functions (February 2, 2026)

- Lecture 7: Introduction to Topology (February 4, 2026)

- Lecture 8: Open and Closed Sets (February 6, 2026)

- Lecture 9: Connected and Path-Connected Sets (February 9, 2026)

- Lecture 10: Compact Sets (February 11, 2026)

- Lecture 11: Riemann Sphere and Complex Derivatives (February 13, 2026)

- Analyticity

- Lecture 12: Cauchy-Riemann Equations (February 18, 2026)

- Lecture 13: Conformal Maps (February 20, 2026)

Lecture 1: Introduction (January 21, 2026)

Complex analysis is especially useful for computing some integrals that are difficult in $\mathbb R$, but easily computed in $\mathbb C$. This is useful for all sorts of domains, including mechanics, statistics (integrating the CDF of a normal distribution), and combinatorics.

Definition (Extended Complex Plane). Just the complex plane and infinity. Formally, $\hat{\mathbb{C}} = \mathbb{C} \cup \set{\infty}$.

Can be modeled by Riemann sphere.

Lecture 2: Operations on $\mathbb{C}$ (January 23, 2026)

$\mathbb{C} = \set{a + bi; a, b \in \mathbb{R}}$, where $i^2 = -1$. This is isomorphic to $\set{(a, b); a, b, \in \mathbb{R}}$, which is isomorphic to $\mathbb{R}^2$. In general, a complex number $x + yi$ can be thought of as a linear combination of two basis vectors, $1$ and $i$. (Equivalently, a complex number $(x, y)$ is the linear combination $x(1, 0) + y(0, 1)$.)

Addition on $\mathbb{C}$ is performed coordinate-wise.

Definition (Real and Imaginary Parts). For $z \in \mathbb{C}$, $z = x+yi$, $\text{Re}(z) = x$ and $\text{Im}(z) = y$.

A complex number can be purely real or purely imaginary.

Multiplication on $\mathbb{C}$

Definition (Multiplication of Complex Numbers). $(a_1, b_1) \times (a_2, b_2) = (a_1a_2 - b_1b_2, a_1b_2 + a_2b_1)$. This is equivalently (and more easily) defined by the following properties: $1 \times 1 = 1$, $1 \times i = i$, $i \times i = -1$.

We might care to define a multiplicative inverse of $z$ such that $z \times z^{-1} = 1$.

Definition (Multiplicative Inverse). If $z = x + yi$, then $\text{Re}(z^{-1}) = \frac{x}{x^2 + y^2}$ and $\text{Im}(z^{-1}) = \frac{-y}{x^2 + y^2}$. Notably, this is only defined when $z \neq 0$.

It follows that $\mathbb{C}$ is a field! It is also algebraically closed, which is essentially the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra.

Proposition. For any $z \in \mathbb{C}$, there exists $w \in \mathbb{C}$ such that $w^2 = z$.

Polar Coordinates

A complex number $z$ can be equivalently represented by $\vert {z} \vert = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}$ and $\text{arg}(z) \in [0, 2 \pi)$, where $\text{arg}(z)$ is essentially the angle between the positive $\mathbb{R}$-axis and $z$. The argument is only defined for $z \neq 0$.

Lecture 3: Multiplication and Polar Coordinates (January 26, 2026)

What is the argument of $z + w$?

Polar coordinates are expecially useful for multiplication, $z \cdot w = r_1 \cdot r_2(\cos(\theta_1 + \theta_2) + i\sin(\theta_1 + \theta_2))$. So $\vert z \cdot w \vert = r_1 \cdot r_2$. And $\text{arg}(z\cdot w) = \text{arg}(z) + \text{arg}(w) \pmod{2\pi}$.

This structure looks familiar! Notably, the logarithm behaves similarly: $\ln(ab) = \ln(a) + \ln(b)$. This will eventually motivate the complex exponential function: $e^{i \theta} = \cos \theta + i \sin \theta$.

What is multiplication?

Multiplication by 2, for example, scales the magnitude of the vector in the complex plane by 2.

Multiplying by $i$ is a rotation by $\frac{\pi}{2}$ anti-clockwise about the origin.

Lecture 4: Complex Functions (January 28, 2026)

In general, $\text{Re}(z) = \frac{z + \bar z}{2}$ and $\text{Im}(z) = \frac{z - \bar z}{2i}$.

The Complex Exponential Function

The exponential function, $f(x) = e^x$, is well-studied over real-valued inputs. It adheres to properties such as:

- $e^{x + y} = e^xe^y$.

- Strictly increasing and positive.

- $f’(x) = e^x$ (the function is its own derivative!).

How to define $e^z$, where $z$ might be a complex number with an imaginary part? Clearly, $e^z = e^{\text{Re}(z)}e^{i\text{Im}(z)}$, but what is $e^{i\text{Im}(z)}$?

Definition (Complex Exponential Function). $e^{iy} = \cos(y) + i \sin(y)$.

Complex Functions

A complex function $f$ acts on $\mathbb{C}$. If it is also defined over real-values, $\mathbb{R}$, the definition of $f$ for $\mathbb{C}$ must be consistent with the restriction of $f$ to $\mathbb{R}$. It is easy enough to verify that $e^z$ when $z$ is real is undisturbed by our definition for $e^z$ for complex-valued inputs.

Other complex functions include $\sin(z) = \frac{e^{iz} - e^{-iz}}{2i}$ and $\cos(z) = \frac{e^{iz} + e^{-iz}}{2}$. It should be easy enough to verify that classic identities and properties of trigonometric functions still hold (for example, $\sin^2(z) + \cos^2(z) = 1$). (Notice that $\vert \cos(z)\vert$ may very well be $>1$! Consider $z = 3i$.)

Lecture 5: Complex Inverses (January 30, 2026)

Over real-valued inputs, $f(x) = e^x$ is a bijective map $\mathbb{R} \to {\mathbb{R}}^{>0}$. However, over complex-valued inputs, $e^0 = e^{2 \pi i}$, so $e^x$ is no longer injetive, and therefore no longer bijective. In order to still define an inverse function $f^{-1}(x)$, we restrict our consideration of $f(x)$ to $f(x)$ on some specific domain. Specifically, let $A_{y_0} = \set{z \in \mathbb{C}: y_0 \leq \text{Im}(z) < y_0 + 2\pi}$. Over inputs from $A_{y_0}$, $e^x$ is a bijective map to $\mathbb{C} \backslash \set{0}$.

Definition (Principle Branch of Logarithm). $\text{Log}(z): \mathbb{C} \backslash \set{0} \to A_0$. Specifically, $\log(z) = \log(\vert z \vert) + i \text{arg}(z)$. In other words, the inverse of $e^x: A_0 \to \mathbb{C} \backslash \set{0}$.

Note that $\log$ denotes the natural logarithm (logarithm with base $e$).

Lecture 6: Graphing Complex Functions (February 2, 2026)

- Plot $w = z^2$.

- Plot $w = e^z$.

- Given $\cos z = \frac{1}{2}$, solve for $z$.

Lecture 7: Introduction to Topology (February 4, 2026)

What is the definition of continuity at a point?

$f(x)$ is continuous at $x = a$ iff, for all $\epsilon > 0$, there exiests $\delta > 0$ such that $\vert x - a \vert < \delta$ implies $\vert f(x) - f(x) \vert < \epsilon$.

Geometrically, continuity implies $f(\mathbb{D}(\alpha; \delta)) \subseteq \mathbb{D}(f(\alpha);\epsilon)$. Equivalently, $\mathbb{D}(\alpha; \delta) \subseteq f^{-1}(\mathbb{D}(f(\alpha);\epsilon))$. (Note that, here, $f^{-1}$ is used to denote the pre-image, and does not imply that $f^{-1}$ is invertible.)

Thus, a function is continuous at $\alpha$ if, for all $\epsilon > 0$, there exists $\mathbb{D}(\alpha; \delta) \subseteq f^{-1}(\mathbb{D}(f(\alpha);\epsilon))$. By definition, a function is continuous at $\alpha$ if, for all $\epsilon > 0$, $f^{-1}(\mathbb{D}(f(\alpha);\epsilon))$ is open.

Lecture 8: Open and Closed Sets (February 6, 2026)

Some open sets:

- $\mathbb{C}$.

- $\varnothing$.

- Arbitrary union of open sets.

- Finite intersection of open sets.

What is an example of an infinite intersection of open sets that is not open?

The intersection of $U_n$, where $U_n = \mathbb{D}(0; 1 +\frac{1}{n})$.

A set, $B$, is closed if its complement, $\mathbb{C} \backslash B$, is open.

Some closed sets:

- $\mathbb{C}$.

- $\varnothing$.

- Arbitrary intersection of closed sets.

- Finite union of closed sets.

Notice that both $\mathbb{C}$ and $\varnothing$ are open and closed (they’re clopen!).

Let’s define a closed disk to be $\overline{\mathbb{D}}(z; r) = \set{w: \vert z - w \vert \leq r}$.

What are equivalent definitions of closedness?

TODO.

What are equivalent definitions of continuity?

TODO.

Lecture 9: Connected and Path-Connected Sets (February 9, 2026)

What is the definition of a path-connected set?

$C \subseteq \mathbb{C}$ is path-connected iff $\forall a, b \in C$, $\exists$ a continuous map $\gamma: [0, 1] \to C$ such that $\gamma(0) = a$ and $\gamma(1) = b$. Note that the image of $\gamma$ must be contained within $C$.

Some path-connected sets:

- $\mathbb{C}$, $\varnothing$.

- Open disks.

- Closed disks.

- Circles.

- Half-planes.

Some non-path-connected sets:

- $\set{i + 1, 0}$.

- In general, union of disjoint sets, $A \sqcup B$.

A path-connected set is connected, but a connected set is not necessarily path-connected.

What three conditions must be true for $C$ to be not connected?

There exists open sets, $U$, and $V$, contained in $\mathbb{C}$, such that:

- $C \subseteq U \cup V$.

- $C \cap U \neq \varnothing$ and $C \cap V \neq \varnothing$.

- $(C \cap U)\cap(C \cap V) = \varnothing$.

Otherwise, $C$ is connected.

If $f$ is a continuous function, and $C$ is connected, then $f(C)$ is connected as well.

Lecture 10: Compact Sets (February 11, 2026)

What is an open cover of a set?

The set of open sets, $\set{U_{\alpha}}$, is open cover of $X$ iff $X \subseteq \bigcup_{\alpha} U_{\alpha}$.

$K$ is a compact set iff every open cover of $K$ has a finite sub-cover. For example, a set $\set{x_1, x_2, \ldots, x_n}$ of finite size is compact. $\mathbb{C}$ is not compact.

What are the two other equivalent equivalent definitions of compactness?

- $K$ is closed and bounded.

- Every sequence $\set{z_n} \subseteq K$ has a convergent subsequence.

If $K$ is compact, and $f: K \to \mathbb{C}$ is continuous$, then $f$ attains finite maximum and minimum values. (what does this mean?)

Consider, $\frac{1}{x}$ on $(0, \infty)$. The maximum and minimum values are not achievable.

Lecture 11: Riemann Sphere and Complex Derivatives (February 13, 2026)

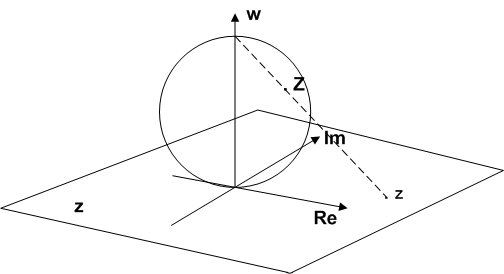

$\mathbb{C}$ is not compact. However, $\hat{\mathbb{C}} = \mathbb{C} \cup \set{\infty}$ is compact. $\hat{\mathbb{C}}$ can be conceptualized as a sphere — the Riemann sphere. Each point, $z$, on the complex plane corresponds to the point on the Riemann sphere where a ray from $\infty$, going through $z$, intersects the sphere.

Visualizing the Riemann Sphere

Analyticity

When is $f: A \to \mathbb{C}$ for some open set $A \in \mathbb{C}$ complex differentiable at $z_0$?

TODO.

Also known as holomorphic on $A$. Specifically, the limit must exist and be equal from all directions. (Check limit from the real direction, and limit from the imaginary direction.)

If $f’(z_0)$ exists, $f$ is continuous at $z_0$. The product rule, quotient rule, and chain rule from real analysis remain basically the same.

Lecture 12: Cauchy-Riemann Equations (February 18, 2026)

$A \subseteq \mathbb{C}$ is an open set. $f: A \to \mathbb{C}$. $f’(z_0)$ exists iff $f$ is differentiable as an $\mathbb{R}$-function at $(x_0, y_0)$ and $\frac{\partial u}{\partial x} = \frac{\partial v}{\partial y}$ and $\frac{\partial u}{\partial y} = -\frac{\partial v}{\partial y}$.

Derive the Cauchy-Riemann equations.

TODO.

Lecture 13: Conformal Maps (February 20, 2026)

A conformal map preserves angles (but not necessariliy lengths). For linear maps, rotating and scaling are conformal.

Any conformal map is of the form $re^{i \theta}$, corresponding to the transforms

\[\begin{bmatrix} r & 0\\ 0 & r \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \cos \theta & -\sin \theta\\ \sin \theta & \cos \theta \end{bmatrix}\]If $f(z)$ is analytic, approximate $f(z) = f(z_o) + (z - z_0)f’(z_0)$ around $z_0$. Suppose $m_w: z \mapsto wz$.

Theorem (Conformal Mapping Theorem). If $f: A \to \mathbb{C}$ is analytic, and $f’(z_0) \neq 0$, then $f$ is conformal with $\theta = \text{arg}f’(z_0)$ and $r = \vert f’(z_0) \vert$.

A conformal map is a holomorphic map with a non-zero derivative.